Tang Dynasty Tiger Reverse Painting Glass Globe Crystal Art Collection

| The Azure Dragon depicted on the flag of the Qing dynasty | |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Dragon |

| Sociology | Chinese mythology |

| State | China |

| Chinese dragon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

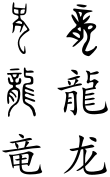

"Dragon" in oracle os script (top left), bronze script (top right), seal script (heart left), Traditional (center correct), Japanese new-style (shinjitai, lesser left), and Simplified (bottom right) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Chinese dragon, as well known as loong , long or lung , is a legendary fauna in Chinese mythology, Chinese folklore, and Chinese culture at large. Chinese dragons have many creature-similar forms such as turtles and fish, but are most commonly depicted equally snake-like with four legs. Academicians have identified iv reliable theories on the origin of the Chinese dragon: snakes, Chinese alligators, thunder and nature worship.[1] They traditionally symbolize potent and auspicious powers, particularly control over water, rainfall, typhoons, and floods. The dragon is as well a symbol of power, forcefulness, and adept luck for people who are worthy of it in East Asian culture.[ citation needed ] During the days of Imperial Prc, the Emperor of Communist china normally used the dragon as a symbol of his imperial strength and power.[2] [ unreliable source? ] In Chinese culture, splendid and outstanding people are compared to a dragon, while incapable people with no achievements are compared to other, disesteemed creatures, such as a worm. A number of Chinese proverbs and idioms feature references to a dragon, such equally "Hoping one's kid will become a dragon" (simplified Chinese: 望子成龙; traditional Chinese: 望子成龍; pinyin: wàng zǐ chéng lóng ).

The impression of dragons in a big number of Asian countries has been influenced by Chinese culture, such as in Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Chinese tradition has always used the dragon totem as the national emblem, and the "Yellow Dragon flag" of the Qing Dynasty has influenced the impression that China is a dragon in many European countries. The white dragon of the flag of modern Bhutan is a archetype Chinese-style dragon.[three]

Affiliated Chinese surnames include 龐 / 庞 (Dragon God, Business firm of Dragon) and 龍 / 龙 (Dragon).

Symbolic value [edit]

Dragon imagery on an eaves-tile

Historically, the Chinese dragon was associated with the Emperor of People's republic of china and used as a symbol to represent regal ability. The founder of the Han dynasty Liu Bang claimed that he was conceived after his mother dreamt of a dragon.[iv] During the Tang dynasty, Emperors wore robes with dragon motif as an imperial symbol, and high officials might also be presented with dragon robes.[5] In the Yuan dynasty, the two-horned five-clawed dragon was designated for utilise by the Son of Heaven or Emperor but, while the four-clawed dragon was used by the princes and nobles.[6] Similarly during the Ming and Qing dynasty, the five-clawed dragon was strictly reserved for use by the Emperor only. The dragon in the Qing dynasty appeared on the first Chinese national flag.[7]

The image of the Chinese dragon was roughly established in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, but at that place was no great change for a long time. In the Han Dynasty, the winged Yinglong, as a symbol of feudal imperial power, oft appeared in Royal Dragon vessels, which means that most of the dragon paradigm designs used by the royal family in the Han Dynasty are Yinglong patterns.Yinglong is a winged dragon in aboriginal Chinese fable. At present, the literature records of Yinglong'south winged image can be tested from "Guangya" ( 廣雅 ) during the 3 Kingdoms period, just Yinglong'south winged blueprint has been establish in bronze ware from the Shang and Zhou Dynasties to rock carvings, silk paintings and lacquerware of the Han Dynasty. The literature records of Yinglong can be traced dorsum to the documents of the pre-Qin period, such equally Classic of Mountains and Seas and Chuci. According to the records in Archetype of Mountains and Seas, the Chinese mythology 2200 years ago, Yinglong had the chief characteristics of later Chinese dragons – the ability to command the sky and the noble mythical status.[8]

Yet, since the Tang and Vocal Dynasties, the image of the real dragon symbolizing China'south regal power was no longer the Yinglong with wings, but the common wingless Yellow Dragon in modern times. For the evolution of Yinglong and Yellow Dragon, scholar Chen Zheng proposed in "Yinglong – the origin of the image of the real dragon" that from the middle of the Zhou Dynasty, Yinglong's wings gradually became the form of flame pattern and deject design at the dragon's shoulder in creative creation, which derived the wingeless long snake shape. The image of Huanglong was used together with the winged Yinglong. Since and then, with a series of wars, Chinese civilization suffered heavy losses, resulting in the forgetting of the epitome of winged Yinglong, and the image of wingless Yellowish Dragon replaced the original Yinglong and became the real dragon symbolizing China's imperial power. On this footing, scholar Xiao Congrong put frontwards that the simplified creative creation of Yinglong'due south wings by Chinese ancestors is a continuous process, that is, the simplification of dragon'south wings is an irreversible trend. Xiao Congrong believes that the phenomenon of "Yellow Dragon" replacing "Ying Long" tin not exist avoided regardless of whether Chinese civilization has suffered disaster or non.[8]

The dragon is sometimes used in the West as a national emblem of China though such apply is not commonly seen in the People's Commonwealth of China or the Democracy of Cathay. Instead, information technology is generally used as the symbol of culture. In Hong Kong, the dragon was a component of the coat of arms under British rule. Information technology was later to go a feature of the pattern of Brand Hong Kong, a regime promotional symbol.[9]

The Chinese dragon has very unlike connotations from the European dragon – in European cultures, the dragon is a fire-animate animal with aggressive connotations, whereas the Chinese dragon is a spiritual and cultural symbol that represents prosperity and good luck, besides as a rain deity that fosters harmony. It was reported that the Chinese government decided against using the dragon as its official 2008 Summer Olympics mascot because of the aggressive connotations that dragons have outside of China, and chose more "friendly" symbols instead.[x] Sometimes Chinese people use the term "Descendants of the Dragon" (simplified Chinese: 龙的传人; traditional Chinese: 龍的傳人) as a sign of ethnic identity, as function of a tendency started in the 1970s when unlike Asian nationalities were looking for animate being symbols as representations, for example, the wolf may be used by the Mongols as information technology is considered to be their legendary ancestor.[four] [7] [11]

As a land symbol [edit]

The dragon was the symbol of the Chinese emperor for many dynasties. During the Qing dynasty, the Azure Dragon was featured on the kickoff Chinese national flag. It was featured once again on the Twelve Symbols national emblem, which was used during the Republic of Mainland china, from 1913 to 1928.

-

-

Flag of the Commissioner of Weihaiwei with the Chinese dragon in the center, 1899–1903

-

A golden Chinese dragon supported the colonial arms of Hong Kong to the correct until its abandonment in 1997.

-

A yellow Chinese dragon carried a shield, emblazoned similar those depicted on the arms of Portugal, in the Macanese Glaze of Artillery under the colonial government until 1999.

Due to influences by Chinese culture, the dragon was also adopted equally state symbol in Vietnam. During the Nguyễn dynasty, the dragon was featured on the imperial standards. It was also featured on the coats of arms of the State of Vietnam, and later South Vietnam.

-

Imperial pennon of Nguyễn dynasty, 1802–1945

-

Vertical royal pennon of Nguyễn dynasty

-

Personal arms of Bảo Đại

-

Coat of Arms of the State of Vietnam, 1954–1955

-

Personal standard of Bảo Đại equally the Chief of Country of Vietnam, 1948–1955

-

The Chinese dragon was used as the supporters of the coat of arms of South Vietnam, 1967–1975

Dragon worship [edit]

Origin [edit]

The ancient Chinese cocky-identified equally "the gods of the dragon" because the Chinese dragon is an imagined reptile that represents evolution from the ancestors and qi energy.[12] Dragon-like motifs of a zoomorphic composition in reddish-brown stone have been establish at the Chahai site (Liaoning) in the Xinglongwa culture (6200–5400 BC).[13] The presence of dragons within Chinese culture dates back several thousands of years with the discovery of a dragon statue dating back to the fifth millennium BC from the Yangshao civilization in Henan in 1987,[xiv] and jade badges of rank in coiled form take been excavated from the Hongshan culture circa 4700–2900 BC.[15] Some of the earliest Dragon artifacts are the pig dragon carvings from the Hongshan civilization.

The coiled dragon or snake form played an of import role in early Chinese culture. The graphic symbol for "dragon" in the primeval Chinese writing has a similar coiled grade, as do after jade dragon amulets from the Shang menstruum.[16]

Ancient Chinese referred to unearthed dinosaur bones every bit dragon bones and documented them equally such. For case, Chang Qu in 300 BC documents the discovery of "dragon bones" in Sichuan.[17] The mod Chinese term for dinosaur is written as 恐龍; 恐龙; kǒnglóng ('terror dragon'), and villagers in key Cathay take long unearthed fossilized "dragon bones" for use in traditional medicines, a practice that continues today.[18]

The binomial proper noun for a variety of dinosaurs discovered in People's republic of china, Mei long, in Chinese ( 寐 mèi and 龙 lóng ) ways 'sleeping dragon'. Fossilized remains of Mei long take been found in China in a sleeping and coiled course, with the dinosaur nestling its snout below one of its forelimbs while encircling its tail around its unabridged trunk.[nineteen]

Mythical brute [edit]

From its origins as totems or the stylized depiction of natural creatures, the Chinese dragon evolved to become a mythical animate being. The Han dynasty scholar Wang Fu recorded Chinese myths that long dragons had nine anatomical resemblances.

The people paint the dragon's shape with a equus caballus'due south head and a serpent's tail. Further, there are expressions every bit 'three joints' and 'nine resemblances' (of the dragon), to wit: from head to shoulder, from shoulder to breast, from breast to tail. These are the joints; equally to the nine resemblances, they are the post-obit: his antlers resemble those of a stag, his caput that of a camel, his optics those of a demon, his neck that of a serpent, his belly that of a mollusk (shen, 蜃 ), his scales those of a carp, his claws those of an eagle, his soles those of a tiger, his ears those of a cow. Upon his caput he has a thing like a broad eminence (a big lump), called [chimu] ( 尺木 ). If a dragon has no [chimu], he cannot ascend to the sky.[20]

Further sources requite variant lists of the nine animate being resemblances. Sinologist Henri Doré lists these characteristics of an authentic dragon: "The antlers of a deer. The head of a crocodile. A demon's optics. The neck of a snake. A tortoise's viscera. A hawk'southward claws. The palms of a tiger. A cow's ears. And it hears through its horns, its ears being deprived of all power of hearing."[21] He notes that, "Others state it has a rabbit's eyes, a frog'south belly, a carp's scales." The anatomy of other legendary creatures, including the bubble and manticore, is similarly amalgamated from violent animals.

Chinese dragons were considered to be physically curtailed. Of the 117 scales, 81 are of the yang essence (positive) while 36 are of the yin essence (negative). Initially, the dragon was chivalrous, wise, and but, but the Buddhists introduced the concept of malevolent influence amidst some dragons. Just as water destroys, they said, and then tin can some dragons destroy via floods, tidal waves, and storms. They suggested that some of the worst floods were believed to have been the result of a mortal upsetting a dragon.

Many pictures of Chinese dragons bear witness a flaming pearl under their chin or in their claws. The pearl is associated with spiritual energy, wisdom, prosperity, power, immortality, thunder, or the moon. Chinese art oftentimes depicts a pair of dragons chasing or fighting over the flaming pearl.

Chinese dragons are occasionally depicted with bat-similar wings growing out of the front limbs, simply almost do not have wings, every bit their ability to fly (and control rain/water, etc.) is mystical and not seen as a effect of their physical attributes.

This description accords with the artistic depictions of the dragon down to the present 24-hour interval. The dragon has too acquired an almost unlimited range of supernatural powers. It is said to exist able to disguise itself as a silkworm, or become as large as our entire universe. It can fly amidst the clouds or hide in h2o (according to the Guanzi). It can form clouds, can turn into water, can change color every bit an power to alloy in with their environs, every bit an effective form of camouflage or glow in the dark (according to the Shuowen Jiezi).

In many other countries, folktales speak of the dragon having all the attributes of the other xi creatures of the zodiac, this includes the whiskers of the Rat, the face up and horns of the Ox, the claws and teeth of the Tiger, the belly of the Rabbit, the body of the Serpent, the legs of the Horse, the goatee of the Caprine animal, the wit of the Monkey, the crest of the Rooster, the ears of the Dog, and the snout of the Squealer.

In some circles, it is considered bad luck to depict a dragon facing downwards, as it is seen every bit disrespectful to place a dragon in such manner that information technology cannot arise to the heaven. Also, depictions of dragons in tattoos are prevalent as they are symbols of strength and power, specially criminal organisations where dragons hold a meaning all on their own. As such, information technology is believed that one must be fierce and stiff enough, hence earning the right to wear the dragon on his pare, lest his luck be consumed by the dragons.[ citation needed ]

According to an art historian John Boardman, depictions of Chinese Dragon and Indian Makara might have been influenced by Kētos in Greek Mythology perhaps afterward contact with silk-route images of the Kētos as Chinese dragon appeared more reptilian and shifted caput-shape afterwards.[22]

Ruler of weather and water [edit]

A dragon seen floating among clouds, on a golden canteen made during the 15th century, Ming dynasty

Chinese dragons are strongly associated with water and atmospheric condition in popular religion. They are believed to be the rulers of moving bodies of water, such equally waterfalls, rivers, or seas. The Dragon God is the dispenser of rain as well equally the zoomorphic representation of the yang masculine power of generation.[23] In this capacity as the rulers of h2o and conditions, the dragon is more than anthropomorphic in grade, oft depicted every bit a humanoid, dressed in a male monarch's costume, but with a dragon head wearing a king'south headdress.

There are four major Dragon Kings, representing each of the Four Seas: the East Sea (corresponding to the East China Sea), the Southward Sea (respective to the South China Ocean), the West Sea (sometimes seen every bit the Qinghai Lake and across), and the N Sea (sometimes seen equally Lake Baikal).

Considering of this association, they are seen as "in charge" of h2o-related weather phenomena. In premodern times, many Chinese villages (especially those close to rivers and seas) had temples dedicated to their local "dragon rex". In times of drought or flooding, information technology was customary for the local gentry and regime officials to lead the community in offering sacrifices and conducting other religious rites to gratify the dragon, either to enquire for rain or a cessation thereof.

The King of Wuyue in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms flow was often known as the "Dragon King" or the "Sea Dragon King" considering of his extensive hydro-engineering schemes which "tamed" the sea.

In coastal regions of China, Korea, Vietnam, traditional legends and worshipping of whales (whale gods) as the guardians of people on the body of water have been referred to Dragon Kings afterward the arrival of Buddhism.[24]

[edit]

According to Chinese legend, both Chinese primogenitors, the primeval Door and the Yellowish Emperor (Huangdi), were closely related to 'Long' (Chinese dragon). At the finish of his reign, the showtime legendary ruler, the Yellow Emperor, was said to have been immortalized into a dragon that resembled his emblem, and ascended to Heaven. The other legendary ruler, the Yan Emperor, was born by his female parent's telepathy with a mythical dragon. Since the Chinese consider the Xanthous Emperor and the Yan Emperor as their ancestors, they sometimes refer to themselves as "the descendants of the dragon". This legend likewise contributed towards the apply of the Chinese dragon as a symbol of majestic power.[ citation needed ]

Dragons (usually with five claws on each pes) were a symbol for the emperor in many Chinese dynasties. During the Qing dynasty, the imperial dragon was colored yellow or gold, and during the Ming dynasty it was cherry.[25] The majestic throne was referred to as the Dragon Throne. During the late Qing dynasty, the dragon was even adopted as the national flag. Dragons are featured in carvings on the stairs and walkways of imperial palaces and imperial tombs, such as at the Forbidden City in Beijing.

In some Chinese legends, an emperor might be born with a birthmark in the shape of a dragon. For instance, 1 fable tells the tale of a peasant born with a dragon birthmark who eventually overthrows the existing dynasty and founds a new ane; another legend might tell of the prince in hiding from his enemies who is identified by his dragon birthmark.[ citation needed ]

In contrast, the Empress of Communist china was often identified with the Chinese phoenix.

Modern belief [edit]

Worship of the Dragon God is celebrated throughout Mainland china with sacrifices and processions during the fifth and sixth moons, and especially on the date of his birthday the thirteenth 24-hour interval of the 6th moon.[23] A folk religious move of associations of good-doing in modern Hebei is primarily devoted to a generic Dragon God whose icon is a tablet with his name inscribed, for which it has been named the "motility of the Dragon Tablet".[26]

Depictions of the dragon [edit]

Neolithic depictions [edit]

Dragons or dragon-like depictions have been constitute extensively in neolithic-period archaeological sites throughout People's republic of china. Some of primeval depictions of dragons were plant at Xinglongwa culture sites. Yangshao culture sites in Xi'an have produced clay pots with dragon motifs. A burial site Xishuipo in Puyang which is associated with the Yangshao civilization shows a big dragon mosaic made out of mollusk shells.[27] The Liangzhu culture also produced dragon-like patterns. The Hongshan civilization sites in present-solar day Inner Mongolia produced jade dragon objects in the form of pig dragons which are the first three-dimensional representations of Chinese dragons.[28]

One such early form was the pig dragon. It is a coiled, elongated animate being with a head resembling a boar.[29] The graphic symbol for "dragon" in the earliest Chinese writing has a similar coiled form, as do later jade dragon amulets from the Shang dynasty. A serpent-like dragon trunk painted on cherry-red pottery wares was discovered at Taosi (Shanxi) from the second phase of the Longshan Culture, and a dragon-like object coated with approximately 2000 pieces of turquoise and jade was discovered at Erlitou.[thirteen]

Classical depictions [edit]

Particular of an embroidered silk gauze ritual garment from a 4th-century BC Zhou era tomb at Mashan, Hubei province, People's republic of china. The flowing, curvilinear design incorporates dragons, phoenixes, and tigers.

Chinese literature and myths refer to many dragons too the famous long. The linguist Michael Carr analyzed over 100 ancient dragon names attested in Chinese archetype texts.[30] Many such Chinese names derive from the suffix -long:

- Tianlong (Chinese: 天龍; pinyin: tiānlóng ; Wade–Giles: t'ien-lung ; lit. 'heavenly dragon'), celestial dragon that guards heavenly palaces and pulls divine chariots; also a proper name for the constellation Draco

- Shenlong (神龍; shénlóng ; shen-lung ; 'god dragon'), thunder god that controls the weather, advent of a homo head, dragon's body, and drum-like tum

- Fuzanglong (伏藏龍; fúcánglóng ; fu-ts'ang-lung ; 'subconscious treasure dragon'), underworld guardian of precious metals and jewels, associated with volcanoes

- Dilong (地龍; dìlóng ; ti-lung ; 'world dragon'), controller of rivers and seas; too a name for earthworm

- Yinglong (應龍; yìnglóng ; ying-lung ; 'responding dragon'), winged dragon associated with rains and floods, used by Yellowish Emperor to kill Chi You lot

- Jiaolong (蛟龍; jiāolóng ; chiao-lung ; 'crocodile dragon'), hornless or scaled dragon, leader of all aquatic animals

- Panlong (蟠龍; pánlóng ; p'an-lung ; 'coiled dragon'), lake dragon that has not ascended to sky

- Huanglong (黃龍; huánglóng ; huang-lung ; 'yellow dragon'), hornless dragon symbolizing the emperor

- Feilong (飛龍; fēilóng ; fei-lung ; 'flying dragon'), winged dragon that rides on clouds and mist; also a name for a genus of pterosaur (compare Feilong kick and Fei Long character)

- Qinglong (青龍; qīnglóng ; ch'ing-lung ; 'Azure Dragon'), the animal associated with the East in the Chinese Four Symbols, mythological creatures in the Chinese constellations

- Qiulong (虯龍; qíulóng ; ch'iu-lung ; 'crimper dragon'), contradictorily defined as both "horned dragon" and "hornless dragon"

- Zhulong (燭龍; zhúlóng ; chu-lung ; 'torch dragon') or Zhuyin (燭陰; zhúyīn ; chu-yin ; 'illuminating darkness') was a giant ruby draconic solar deity in Chinese mythology. It supposedly had a human's face up and snake's trunk, created day and night by opening and endmost its eyes, and created seasonal winds by animate. (Notation that this zhulong is different from the similarly named Vermilion Dragon or the Pig dragon).

- Chilong (螭龍 or 魑龍; chīlóng ; ch'ih-lung ; 'demon dragon'), a hornless dragon or mountain demon

Fewer Chinese dragon names derive from the prefix long-:

- Longwang (龍王; lóngwáng ; lung-wang ; 'Dragon Kings') divine rulers of the Four Seas

- Longma (龍馬; lóngmǎ ; lung-ma ; 'dragon horse'), emerged from the Luo River and revealed ba gua to Fu Eleven

Some additional Chinese dragons are not named with long 龍 , for example,

- Hong (虹; hóng ; hung ; 'rainbow'), a two-headed dragon or rainbow snake

- Shen (蜃; shèn ; shen ; 'behemothic clam'), a shapeshifting dragon or sea monster believed to create mirages

- Bashe (巴蛇; bāshé ; pa-she ; 'ba serpent') was a giant python-like dragon that ate elephants

- Teng (螣; téng ; t'eng ) or Tengshe (腾蛇; 騰蛇; téngshé ; t'eng-she ; lit. "soaring snake") is a flying dragon without legs

Chinese scholars have classified dragons in diverse systems. For example, Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty canonized five colored dragons every bit "kings".

- The Azure Dragon [Qinglong 青龍 ] spirits, most compassionate kings.

- The Vermilion Dragon [Zhulong 朱龍 or Chilong 赤龍 ] spirits, kings that bestow blessings on lakes.

- The Yellowish Dragon [Huanglong 黃龍 ] spirits, kings that favorably hear all petitions.

- The White Dragon [Bailong 白龍 ] spirits, virtuous and pure kings.

- The Blackness Dragon [Xuanlong 玄龍 or Heilong 黑龍 ] spirits, kings dwelling in the depths of the mystic waters.[31]

With the addition of the Yellow Dragon of the Center to Azure Dragon of the East, these Vermilion, White, and Black Dragons coordinate with the Four Symbols, including the Vermilion Bird of the South, White Tiger of the West, and Black Tortoise of the N.

Ix sons of the dragon [edit]

Pulao on a bell in Wudang Palace, Yangzhou

Several Ming dynasty texts list what were claimed as the Ix Offspring of the Dragon ( 龍生九子 ), and subsequently these feature prominently in popular Chinese stories and writings. The scholar Xie Zhaozhe (1567–1624) in his work Wu Za Zu Wuzazu (c. 1592) gives the following list, as rendered past M.W. de Visser:

A well-known work of the end of the sixteenth century, the Wuzazu 五雜俎 , informs us virtually the nine different young of the dragon, whose shapes are used every bit ornaments according to their nature.

- The [pú láo 蒲牢 ], 4 leg small form dragon grade which similar to scream, are represented on the tops of bells, serving as handles.

- The [qiú niú 囚牛 ], which like music, are used to beautify musical instruments.

- The [chī wěn 蚩吻 ], which like swallowing, are placed on both ends of the ridgepoles of roofs (to swallow all evil influences).

- The [cháo fēng 嘲風 ], beasts-like dragon which like adventure, are placed on the 4 corners of roofs.

- The [yá zì 睚眦 ], which like to kill, are engraved on sword guards.

- The [xì xì 屓屭 ], which have the shape of the [chī hǔ 螭虎 (One kind small form dragon)], and are fond of literature, are represented on the sides of grave-monuments.

- The [bì àn 狴犴 ], which similar litigation, are placed over prison gates (in order to keep guard).

- The [suān ní 狻猊 ], which similar to sit down downward, are represented upon the bases of Buddhist idols (nether the Buddhas' or Bodhisattvas' feet).

- The [bì xì 贔屭 ], also known as [bà xià 霸下 ], finally, large tortoises which like to conduct heavy objects, are placed nether grave-monuments.

Further, the same author enumerates 9 other kinds of dragons, which are represented as ornaments of different objects or buildings according to their liking prisons, h2o, the rank aroma of newly caught fish or newly killed meat, wind and rain, ornaments, smoke, shutting the rima oris (used for adorning key-holes), standing on steep places (placed on roofs), and fire.[32]

The Sheng'an waiji ( 升庵外集 ) collection by the poet Yang Shen ( 楊慎 , 1488–1559) gives different fifth and ninth names for the dragon's 9 children: the tāo tiè ( 饕餮 ), form of beasts, which loves to swallow and is constitute on food-related wares, and the jiāo tú ( 椒圖 ), which looks like a conch or clam, does not similar to be disturbed, and is used on the front door or the doorstep. Yang'south list is bì xì, chī wěn or cháo fēng, pú láo, bì àn, tāo tiè, qiú niú, yá zì, suān ní, and jiāo tú. In addition, there are some sayings including [bā xià 𧈢𧏡 ], Hybrid of reptilia animal and dragon, a brute that likes to drink water, and is typically used on bridge structures.[33]

The oldest known attestation of the "children of the dragon" listing is found in the Shuyuan zaji ( 菽園雜記 , Miscellaneous records from the bean garden) by Lu Rong (1436–1494); however, he noted that the list enumerates mere synonyms of diverse antiques, non children of a dragon.[34] The nine sons of the dragon were commemorated by the Shanghai Mint in 2012's year of the dragon with two sets of coins, one in silvery, and ane in contumely. Each coin in the sets depicts one of the 9 sons, including an additional coin for the begetter dragon, which depicts the nine sons on the reverse.[35] Information technology'southward likewise a Chinese idiom, which means among brothers each i has his good points.[ citation needed ]

Dragon claws [edit]

Reverse of statuary mirror, eighth century, Tang dynasty, showing a dragon with three toes on each foot

Early Chinese dragons are depicted with two to five claws. Dissimilar countries that adopted the Chinese dragon take dissimilar preferences; in Mongolia and Korea, four-clawed dragons are used, while in Japan, three-clawed dragons are common.[36] In Prc, three-clawed dragons were popularly used on robes during the Tang dynasty.[37] The usage of the dragon motif was codified during the Yuan dynasty, and the v-clawed dragons became reserved for use by the emperor while the princes used four-clawed dragons.[6] Phoenixes and v-clawed two-horned dragons may non be used on the robes of officials and other objects such every bit plates and vessels in the Yuan dynasty.[6] [38] Information technology was farther stipulated that for commoners, "it is forbidden to clothing whatever textile with patterns of Qilin, Male person Fenghuang (Chinese phoenix), White rabbit, Lingzhi, Five-Toe 2-Horn Dragon, Eight Dragons, Ix Dragons, 'Ten one thousand years', Fortune-longevity character and Golden Yellow etc."[39]

The Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty emulated the Yuan dynasty rules on the use of the dragon motif and decreed that the dragon would be his emblem and that it should take v claws. The four-clawed dragon would be used typically for imperial nobility and sure high-ranking officials. The three-clawed dragon was used by lower ranks and the general public (widely seen on various Chinese goods in the Ming dynasty). The dragon, even so, was merely for select royalty closely associated with the imperial family, usually in diverse symbolic colors, while information technology was a upper-case letter offense for anyone—other than the emperor himself—to e'er use the completely golden-colored, v-clawed Long dragon motif. Improper apply of claw number or colors was considered treason, punishable by execution of the offender's entire clan. During the Qing dynasty, the Manchus initially considered three-clawed dragons the nearly sacred and used that until 1712 when information technology was replaced past five-clawed dragons, and portraits of the Qing emperors were normally depicted with five-clawed dragons.[forty]

In works of fine art that left the imperial collection, either as gifts or through pilfering past court eunuchs (a long-standing problem), where practicable, ane claw was removed from each set, as in several pieces of carved lacquerware,[41] for case the well known Chinese lacquerware tabular array in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[42]

Cultural references [edit]

Number nine [edit]

The number ix is special in China as it is seen equally number of the heaven, and Chinese dragons are frequently connected with information technology. For example, a Chinese dragon is commonly described in terms of nine attributes and commonly has 117 (9×thirteen) scales–81 (9×9) Yang and 36 (9×4) Yin. This is also why there are nine forms of the dragon and there are ix sons of the dragon (run into Classical depictions above). The Ix-Dragon Wall is a spirit wall with images of nine different dragons, and is found in imperial Chinese palaces and gardens. Because nine was considered the number of the emperor, but the about senior officials were allowed to vesture ix dragons on their robes—and then only with the robe completely covered with surcoats. Lower-ranking officials had 8 or five dragons on their robes, again covered with surcoats; fifty-fifty the emperor himself wore his dragon robe with one of its 9 dragons hidden from view.

In that location are a number of places in China called "9 Dragons", the most famous existence Kowloon (in Cantonese) in Hong Kong. The office of the Mekong in Vietnam is known as Cửu Long, with the same pregnant.

Chinese zodiac [edit]

The Dragon is one of the 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac which is used to designate years in the Chinese agenda. It is thought that each animal is associated with certain personality traits. Dragon years are usually the nearly popular to have children.[43] At that place are more people born in Dragon years than in any other animal years of the zodiac.[44]

Constellations [edit]

The Azure Dragon (Qing Long, 青龍 ) is considered to exist the primary of the four celestial guardians, the other three being the Zhu Que —朱雀 (Vermilion Bird), Bai Hu —白虎 (White Tiger), Xuan Wu —玄武 (Black Tortoise-like creature). In this context, the Azure Dragon is associated with the East and the element of Woods.

Dragonboat racing [edit]

Dragon boats racing in Hong Kong (14th century painting)

At special festivals, especially the Duanwu Festival, dragon boat races are an important part of festivities. Typically, these are boats paddled past a team of up to twenty paddlers with a drummer and steersman. The boats take a carved dragon every bit the head and tail of the boat. Dragon boat racing is as well an important part of celebrations outside of China, such as at Chinese New year. A similar racing is popular in Bharat in the state of Kerala chosen Vallamkali and at that place are records on Chinese traders visiting the seashores of Kerala centuries dorsum (Ibn Batuta).[ commendation needed ]

Dragon dancing [edit]

On auspicious occasions, including Chinese New year and the opening of shops and residences, festivities often include dancing with dragon puppets. These are "life sized" cloth-and-wood puppets manipulated by a squad of people, supporting the dragon with poles. They perform choreographed moves to the accompaniment of drums, drama, and music. They also wore skilful clothing made of silk.

Dragon and Fenghuang [edit]

Fenghuang (simplified Chinese: 凤凰; traditional Chinese: 鳳凰; pinyin: fènghuáng ; Wade–Giles: fêngiv-huang2 ), known in Japanese as Hō-ō or Hou-ou, are phoenix-like birds found in East Asian mythology that reign over all other birds. In Chinese symbolism, it is a feminine entity that is paired with the masculine Chinese dragon, as a visual metaphor of a counterbalanced and blissful relationship, symbolic of both a happy marriage and a regent'south long reign.

Dragon as nāga [edit]

Phra Maha Chedi Chai Mongkol Naga emerging from rima oris of Makara

In many Buddhist countries, the concept of the nāga has been merged with local traditions of peachy and wise serpents or dragons, as depicted in this stairway image of a multi-headed nāga emerging from the oral cavity of a Makara in the style of a Chinese dragon at Phra Maha Chedi Chai Mongkol on the premises of Wat Pha Namthip Thep Prasit Vararam in Thailand's Roi Et Province Nong Phok District.[ commendation needed ]

Dragons and tigers [edit]

The tiger is considered to be the eternal rival to the dragon, thus various artworks depict a dragon and tiger fighting an epic battle. A well used Chinese idiom to describe equal rivals (frequently in sports nowadays) is "Dragon versus Tiger". In Chinese martial arts, "Dragon style" is used to describe styles of fighting based more on agreement move, while "Tiger way" is based on creature strength and memorization of techniques.[ citation needed ]

Dragons and botany [edit]

The elm cultivar Ulmus pumila 'Pendula', from northern China, called 'Weeping Chinese Elm' in the Due west, is known locally equally Lung chao yü shu ('Dragon'due south-claw elm') owing to its branching.[45] [46]

In popular culture [edit]

- Equally a part of traditional sociology, dragons announced in a multifariousness of mythological fiction. In the classical novel Journey to the Westward, the son of the Dragon King of the W was condemned to serve as a horse for the travelers because of his indiscretions at a political party in the heavenly court. Sun Wukong'south staff, the Ruyi Jingu Bang, was robbed from Ao Guang, the Dragon King of the East Ocean. In Fengshen Yanyi and other stories, Nezha, the male child hero, defeats the Dragon Kings and tames the seas. Chinese dragons besides appear in innumerable Japanese anime films and television receiver shows, manga, and in Western political cartoons as a personification of the People'southward Republic of People's republic of china. The Chinese respect for dragons is emphasized in Naomi Novik's Temeraire novels, where they were the first people to tame dragons and are treated as equals, intellectuals, or fifty-fifty royalty, rather than beasts solely bred for state of war in the West. Manda is a large Chinese dragon that appears in the Godzilla storyline. A golden three-headed dragon also appears in the comic book series God Is Expressionless.

- Red dragon is a symbol of China which appears in many Mahjong games.

- A Chinese h2o dragon bandage by a mermaid named Aurora is the main antagonist in Season 3 of the Australian television series Mako Mermaids. The Dragon is heavily based on Chinese mythology to coincide with a new Chinese mermaid on the show.

- The main antagonist of Wendy Wu: Homecoming Warrior, Yan-Lo, was a Chinese dragon. Despite the fact that he's deceased during the events of the motion picture, he continues to hatch evil plans in the course of a spirit.

- In Monster High, Jinafire Long is the daughter of a Chinese dragon.

- Mushu, a character from Disney'south Mulan and its sequel.

- In the Marvel Cinematic Universe movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, the Corking Protector is a Chinese water dragon that protects the realm of Ta Lo.

Regional variations across Asia [edit]

While depictions of the dragon in fine art and literature are consistent throughout the cultures in which it is found, there are some regional differences.

For more data on peculiarities in the delineation of the dragon in E Asian, S Asian, and Southeast Asian cultures, see:

- Dragons related to the Chinese dragon

- Druk, the Thunder Dragon of Bhutanese mythology

- the Japanese dragon

- the Korean dragon

- Nāga, a Hindu and Buddhist animate being in South Asian and Southeast Asian mythology.

- Bakunawa, a moon-eating bounding main dragon depicted in Philippine mythology.

- Pakhangba, a Manipuri dragon.

- the Vietnamese dragon

- Dragons similar to the Chinese dragon

- Makara, a sea Dragon in Hindu and Buddhist mythology

- Yali, a legendary creature in Hindu mythology

- the Nepalese dragon as depicted with Bhairava, likewise known as the "flying snake"

Gallery [edit]

Architecture [edit]

-

-

-

Stone relief of dragons between a flying of stairs in the Forbidden City

Textile [edit]

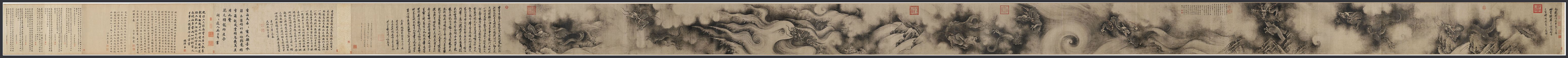

Painting [edit]

-

-

Dragon clouds and waves, 16th-17th century

Metalwork [edit]

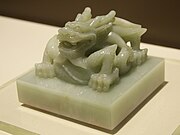

Jade [edit]

-

-

Jade seal with dragon handle

-

Jade vase

Ceramics [edit]

Mod artwork [edit]

-

Mini-Sculpture of a Dragon on pinnacle of a temple in Hsinchu, Taiwan

-

The Chinese dragon statue at Vihara Dharmayana Kuta, Bali, Indonesia

See likewise [edit]

- An Instinct for Dragons, hypothesis well-nigh the origin of dragon myths.

- Chinese alligator

- Chinese mythology

- Fish in Chinese mythology

- Lei Chen-Tzu

- List of dragons in mythology and folklore

- List of dragons in popular culture

- Long Mu (Dragon's Mother)

- Radical 212

- Snakes in Chinese mythology, mostly about less dragon-like types

- People's republic of china Dragon – hockey team playing in the Asia League Ice Hockey

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Meccarelli, Marco (2021). "Discovering the Long : Current Theories and Trends in Research on the Chinese Dragon". Frontiers of History in Mainland china. sixteen (one): 123–142. doi:10.3868/s020-010-021-0006-6 (inactive 28 February 2022). ISSN 1673-3401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive equally of February 2022 (link) - ^ Ingersoll, Ernest; et al. (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books.

- ^ Congrong Xiao.Universal Culture in Europe and Asia——A Brief Analysis of the History of Universal Culture in Ancient Rome and China[J].International Journal of Frontiers in Sociology,2021(ten):109-115.

- ^ a b Dikötter, Frank (10 November 1997). The Construction of Racial Identities in Communist china and Japan. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. pp. 76–77. ISBN978-1850652878.

- ^ "Majestic Dragons". Kyoto National Museum. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Linda Komaroff, ed. (2006). Across the Legacy of Genghis Khan. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 320. ISBN978-9047418573.

- ^ a b Sleeboom, Margaret (2004). Bookish Nations in China and Nippon Framed in concepts of Nature, Culture and the Universal. Routledge publishing. ISBN 0-415-31545-Ten

- ^ a b XiaoCongRong.探究中华龙纹设计的历史流变(Exploring the historical evolution of Chinese dragon blueprint)[J].今古文创,2021(46):92-93.

- ^ "Brand Overview", Brand Hong Kong, 09-2004 Retrieved 23 February 2007. Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Fiery Debate Over Mainland china'south Dragon", BBC News, an commodity roofing China's decision not to apply a dragon mascot and the resulting thwarting.

- ^ "The Mongolian Message". Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Dr Zai, J. Taoism and Science: Cosmology, Development, Morality, Health and more. Ultravisum, 2015.

- ^ a b Meccarelli, Marco (2021). "Discovering the Long : Current Theories and Trends in Research on the Chinese Dragon". Frontiers of History in China. Frontiers of History in Mainland china vol. 16 issue 1. xvi (1): 123–142. doi:10.3868/s020-010-021-0006-6#i (inactive 28 Feb 2022). ISSN 1673-3401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2022 (link) - ^ Howard Giskin and Bettye S. Walsh (2001). An introduction to Chinese culture through the family. State University of New York Press. p. 126. ISBN0-7914-5047-three.

- ^ "Teaching Chinese Archeology" Archived 11 Feb 2008 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Fine art, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Salviati, Filippo (2002). The Linguistic communication of Adornment: Chinese Ornaments of Jade, Crystal, Amber and Glass, Fig. 17. 10 Speed Press. ISBN 1-58008-587-iii.

- ^ Dong Zhiming (1992). Dinosaurian Faunas of China. Mainland china Ocean Press, Beijing. ISBN3-540-52084-viii. OCLC 26522845.

- ^ "Dinosaur basic 'used as medicine'". BBC News Online. half-dozen July 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ Xu and Norell, (2004). "A new troodontid dinosaur from Communist china with avian-like sleeping posture". Nature, 431(7010): 838–841. doi:x.1038/news041011-7

- ^ de Visser, Marinus Willem (1913). "The Dragon in China and Nihon". Verhandelingen der Koninklijke akademie van wetenschappen te Amsterdam. Afdeeling Letterkunde. Nieuwe reeks, deel xiii, no. 2. Amsterdam: Johannes Müller: 70. (Also available at University of Georgia Library Archived 2016-12-25 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Doré, Henri (1966) [1917]. Researches into Chinese Superstitions. Translated by M. Kennelly; D. J. Finn; L. F. McGreat. Ch'eng-wen. p. 681.

- ^ Boardman, John (2015). The Greeks in Asia. Thames and Hudson. ISBN978-0500252130.

- ^ a b Tom (1989), p. 55.

- ^ 李 善愛, 1999, 護る神から守られる神へ : 韓国とベトナムの鯨神信仰を中心に, pp.195-212, 国立民族学博物館調査報告 Vol.149

- ^ Hayes, L. (1923). The Chinese Dragon. Shanghai, China: Commercial Press Ltd. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/chinesedragon00hayeuoft#page/n7/mode/2up

- ^ Zhiya Hua. Dragon's Name: A Folk Religion in a Village in South-Central Hebei Province. Shanghai People's Publishing House, 2013. ISBN 7208113297

- ^ Hung-Sying Jing; Allen Batteau (2016). The Dragon in the Cockpit: How Western Aviation Concepts Conflict with Chinese Value Systems. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN978-1317035299.

- ^ John Onians (26 April 2004). Atlas of World Fine art. Laurence King Publishing. p. 46. ISBN978-1856693776.

- ^ "Jade coiled dragon, Hongshan Civilisation (c. 4700–2920 B.C.)" Archived 13 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Retrieved 23 Feb 2007.

- ^ Carr, Michael. 1990. "Chinese Dragon Names", Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Expanse xiii.two:87–189. He classified them into seven categories: Rain-dragons, Flight-dragons, Snake-dragons, Wug-dragons [wug refers to "worms, bugs, and modest reptiles"], Crocodile-dragons, Colina-dragons, and Miscellaneous dragons.

- ^ Adjusted from Doré 1966, p. 682.

- ^ de Visser 1913, pp. 101–102. The master source is Wu Za Zu, affiliate ix, beginning with " 龍生九子... ". The championship of Xie Zhaozhe's work, Wu Za Zu, has been variously translated into English as V Assorted Offerings (in Xie Zhaozhe), Five Sundry Bands (in "Disease and Its Impact on Politics, Diplomacy, and the Military machine ...") or V Miscellanies (in Changing clothes in Red china: fashion, history, nation, p. 48).

- ^ 吾三省 (Wu Sanxing) (2006). 中國文化背景八千詞 (Eight thousand words and expressions viewed against the groundwork of Chinese culture) (in Chinese). 商務印書館(香港) (Commercial Press, Hong Kong). p. 345. ISBN962-07-1846-ane.

- ^ 九、龙的繁衍与附会 – 龙生九子 (1) ("Chapter 9, Dragon'south derived and associated creatures: Nine children of the dragon (1)"), in Yang Jingrong and Liu Zhixiong (2008). The full text of Shuyuan zaji, from which Yang and Liu quote, is available in electronic format at a number of sites, e.g. here: 菽園雜記 Archived 6 March 2010 at the Wayback Car

- ^ CCT4243: 2012 lunar dragon nine sons of the dragon 20 money prepare Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Famous Japanese Dragons". 9 January 2021.

- ^ Michael Sullivan (1992). The Arts of People's republic of china. University of California Press. p. 214. ISBN978-0520049185.

- ^ 《志第二十八 輿服一》. The History of Yuan.

- ^ 《本紀第三十九 順帝二》. The History of Yuan, Emperor Shundi ( 元史·順帝紀) , compiled under Song Lian ( 宋濂 ), Advertizement 1370.

禁服麒麟、鸞鳳、白兔、靈芝、雙角五爪龍、八龍、九龍、萬壽、福壽字、赭黃等服

- ^ Roy Bates (2007). All Almost Chinese Dragons. p. twenty–21. ISBN978-1435703223.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Fine art, p. 177, 2007 (2d edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0714124469

- ^ Clunas, Craig and Harrison-Hall, Jessica, Ming: 50 years that inverse China, p. 107, 2014, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0714124841

- ^ "Why Chinese children born in years of the dragon are more than successful". The Economist. 4 September 2017.

- ^ Mocan & Yu, Naci H. & Han (May 2019) [Baronial 2017]. "Can Superstition Create a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? School Outcomes of Dragon Children of China" (PDF). The National Bureau of Economic Enquiry (NBER Working Paper No. 23709): xiii, 47. Retrieved 3 Dec 2019.

- ^ U. pumila 'Pendula', 'Inventory of Seeds and Plants Imported ... Apr–June 1915' (March 1918), ars-smile.gov/npgs/pi_books/scans/pi043.pdf

- ^ U. pumila 'Pendula', 中国自然标本馆. Cfh.ac.cn. Retrieved 30 Baronial 2013.

Sources [edit]

- Nikaido, Yoshihiro (2015). Asian Folk Organized religion and Cultural Interaction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN978-3847004851.

- Overmyer, Daniel L. (2009). Local Organized religion in North Red china in the Twentieth Century: The Structure and Arrangement of Community Rituals and Behavior. Brill. ISBN978-9004175921.

- Tom, Chiliad. South. (1989). Echoes from Old Mainland china: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Center Kingdom . University of Hawaii Press. ISBN0824812859.

External links [edit]

-

Quotations related to Chinese dragon at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Chinese dragon at Wikiquote

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_dragon

0 Response to "Tang Dynasty Tiger Reverse Painting Glass Globe Crystal Art Collection"

Postar um comentário