Why Is It Important to Integrate Both Evidence-based Practice and Patient and Family Preferences?

The Consumer Benefits of Patient Shared Determination Making

From patient-centered medical homes to consumer-directed health plans, changes in the commitment, financing and organization of healthcare are increasingly touted as consumer- or patient-centered. Withal, today'southward wellness arrangement is far from reflecting consumers' truthful needs and preferences.i

Patient shared decision making (PSDM) is a technique to incorporate patients' needs and preferences into their individual treatment plans. PSDM goes beyond traditional informed consent in healthcare—it is an interpersonal, interdependent process in which healthcare providers and patients collaborate to make decisions about the care that patients receive. Shared conclusion making not but reflects medical evidence and providers' clinical expertise, but too the unique preferences and values of patients and their families.

Given that this strategy has considerable advantages and few disadvantages, it is used far too infrequently. Policymakers, payers and health systems should abet for patient shared decision making to be the standard of intendance for all clinical encounters that accept more than i medically appropriate path forward.

This report describes patient shared conclusion making and reviews the evidence supporting its use. Existing challenges and strategies to expand the use of PSDM are also discussed.

What is Patient Shared Decision Making?

Shared decision making is a primal component of patient-centered health care. It is a process whereby clinicians and patients work together to make treatment decisions and select tests, care plans and supportive services in a way that balances clinical show on risks and expected outcomes, with patient preferences and values.2

In that location are three essential elements that must be present for shared decision making to occur:

- Both the healthcare provider and the patient must recognize and acknowledge that a decision is required.

- Both must sympathize the risks and benefits of each selection.

- Decisions must take into account both the provider'south guidance and the patient's values and preferences.iii

For some medical conditions, at that place is only a single treatment path in which patient preferences play a small office. These situations might include a fractured hip repair, surgery for acute appendicitis or antibiotics for bacterial meningitis.4 However, nearly diagnoses have more than than one medically appropriate path frontwards, with different potential outcomes and side furnishings.5 Examples of these circumstances include treatments for early-stage cancer, primary prevention of coronary heart disease and the utilize of genetic and claret screening tests.

When more than one medical treatment exists, clinicians can facilitate shared decision making past encouraging patients to voice their concerns and priorities. They can also offer decision aids to increase patient awareness and understanding of the various treatment options and possible outcomes.

Patient Determination Aids

A well-designed patient decision aid provides actionable data on the risks, benefits and burdens of treatment options, and helps patients identify and communicate their preferences.6 These aids can be spider web-based, printed materials or educational videos that assistance patients understand relevant clinical prove, develop informed preferences and communicate them to their providers.7 A 2011 study showed that conclusion aids perform better than traditional, not-shared decision making care interventions in clinical settings, and significantly improved patients' knowledge of their atmospheric condition and treatment options.8

But shared conclusion making is more than just the employ of determination aids. It requires meaningful clinician-patient date.

Barriers to Effective Patient-Doc Communication

Patient shared decision making requires open and respectful communication between the patient and physician, but myriad factors can undermine this type of exchange. For example, both patient and dr. may approach the conversation with pre-conceived notions that hinder the shared decision-making procedure.

Some patients distrust or feel uncomfortable discussing health concerns with doctors who they cannot relate to on a personal level.9 For example, elderly patients, patients who speak English equally a second language and those with lower literacy levels may feel less engaged in the conclusion-making process and accept less confidence navigating the healthcare system.10 Other patients might come from cultural backgrounds that lack a tradition of individuals making democratic decisions, thus making it difficult for them to appoint with their provider.

Physicians can also unwittingly introduce barriers. Many doctors believe that they are good at identifying patient preferences, but there are enormous gaps betwixt what patients want and what doctors recollect they desire.eleven For example, a physician may believe that a patient with prostate cancer'due south priority is to remove the cancer, while the patient's priority may exist to maintain the best possible quality of life. The misdiagnosis of patient preferences thus becomes a deterrent to delivering patient-centered care.12 Moreover, doctors may unknowingly hold biases toward patients who they feel are not able to understand circuitous medical information.13

Ineffective patient-medico advice tin too exist attributed to the lack of emphasis on communication skills during medical training. Nigh communication grooming takes identify during the preclinical years of medical school in the form of lectures and role plays with patients. During clinical rotations, students take direct encounters with patients, but niggling attention is devoted to communication abilities compared to diagnostic skills.14 Similarly, potent communication skills are often not stressed in postgraduate medical training, leaving residents and practicing physicians to learn to communicate finer on their own.

Bear witness Around Shared Decision Making

The evidence around shared determination making is fairly strong. Shared decision making has been shown to issue in treatment plans that better reflect patients' goals; increase patient and physician satisfaction; improve patient-doc communication; take a positive upshot on outcomes; and, sometimes reduce costs.

Patient and Dr. Satisfaction

Having a forum to voice their preferences and understanding the risks and benefits associated with their decisions makes patients happier with the care they receive. I study constitute that patients who participated in shared decision making were more knowledgeable about their status (compared to a control group) and, when given their treatment of choice, reported college overall quality of life after half dozen months.16 Additionally, these patients were far more likely to be satisfied with their treatment, with well-nigh 71 percent satisfied, compared to virtually 35 percent of patients who did non engage in PSDM.17 Patients who made informed decisions were also less likely to regret their treatment choices (about 5 percent, compared with 15 pct of patients in the command group).18

Shared determination making can besides increase physician satisfaction as a result of feeling that they are supporting and listening to their patients while providing high-quality intendance.xix

Improved Communication

Shared decision-making techniques tin aid patients plant trust with their providers and helps providers engage and meliorate communicate with their patients. A 2013 study assessed the relationship between African American patients and their providers using chat guides to lead patient-medico conversations. Qualitative interview data showed patients' trust in physicians increased after using the conversation guides.20 Researchers farther noted that, while PSDM can increase trust, using other specific techniques in combination with PSDM was particularly effective. Specifically, mistrust of physicians amongst African Americans with diabetes may partially exist addressed through patient education efforts and doctor training in interpersonal skills and cultural competence. Other research shows that, when physicians understand cultural and other personal factors of a patient, the patient is more inclined to trust the provider with their care.21

Positive patient-provider relationships are non only part of expert bedside manner; perceived respect has a strong correlation with whether patients trust doctors to exist accurate and whether they attach to their medications. Thus, strong relationships should exist considered a medical priority and should be encouraged through preparation, educational activity and, potentially, bounty changes.22

Improved Outcomes

Research reveals that patients who are empowered to make healthcare decisions that reflect their personal preferences oftentimes report feeling more engaged in their healthcare and feel better wellness outcomes, similar decreased feet, quicker recovery and increased compliance with treatment regimens.23

A 2017 review of 105 studies showed that use of decision aids reduced the number of patients that were passive in their treatment and increased patient adherence to recommended therapies.24 Patients besides had increased noesis, more accurate perception of risk and reduced internal conflict nigh healthcare decisions.

Reduced Costs

Preference-sensitive conditions, such as treatments for joint arthritis, dorsum pain and early on phase prostate cancer,25 are medical conditions in which the clinical evidence does non clearly back up one treatment selection, and the appropriate course of treatment depends on the values or preferences of the patient.26 People who are fully informed nigh the risks and benefits of treatments and screening for preference-sensitive conditions tend to choose less-invasive, less-costly interventions and are happier with their decisions.27

Concerns have been raised that offer patients more options may increase costs.28 To engagement, the cost of implementing shared decision making has been studied in only a express number of practice settings and typically in relatively pocket-size patient populations.29

One study compared the price of care for an uncomplicated menorrhagia among patients that received a decision aid, patients that received a decision aid followed by a nurse's coaching to arm-twist patient preferences, and a control group. The analysis constitute that a decision assistance, either implemented alone or with coaching, had lower mean costs ($ii,026 and $1,566 respectively) than the control group ($2,751).30

In addition, a 2012 study showed that providing determination aids to patients eligible for hip and knee replacements substantially reduced surgery rates and costs—with up to 38 percent fewer surgeries and a 12 to 21 percent savings over six months.31 Across a few studies, every bit many as 20 percent of patients who participated in shared determination making chose less invasive surgical options and more conservative handling than patients who did not utilise determination aids.32

Nevertheless, more study is needed to understand the cyberspace costs of implementing shared decision making in a variety of treatment scenarios.

Challenges to Expanding the Use of Shared Determination Making

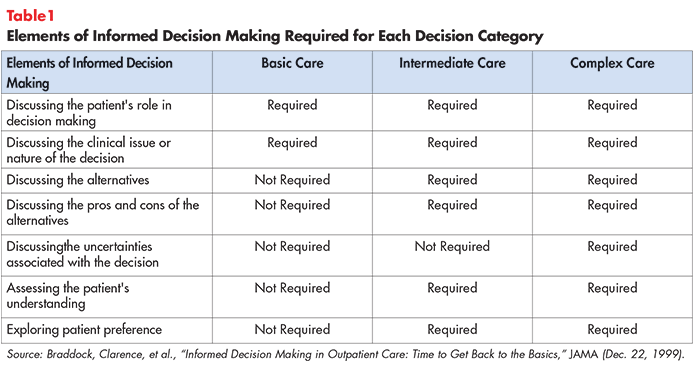

Despite the potential benefits, shared decision making has non been widely implemented in clinical do. Many clinicians discover PSDM difficult to accomplish, and nearly healthcare systems do not view this approach as the standard of care. In a study of more than 1,000 function visits in which more than 3,500 medical decisions were fabricated, less than 10 percent of decisions met the minimum standards for shared decision making (meet Table 1 for elements of informed decision making).33

Some other study showed that simply 41 percent of Medicare patients believed that their treatment reflected their preference for palliative care over more aggressive interventions.34 Additionally, patients report frustration and dissatisfaction because they practice not feel like they have adequate (if whatever) input into clinicians' decisions that bear on their health,35 including not knowing enough about their treatment options to brand informed decisions.

Challenges to expanding the use of shared conclusion making include:

- Belief that PSDM is non appropriate or necessary for provider's specialty;

- decision help shortcomings;

- provider time constraints;

- provider reimbursement non aligned with PSDM;

- provider preparation; and

- malpractice liability

Belief that PSDM is Not Appropriate or Necessary for Provider's Specialty

A systematic review of barriers to PSDM institute that many physicians perceive PSDM to be inappropriate for their patients or clinical specialty.36 Health professionals' trend to determine which patients will prefer or do good from shared determination making is concerning because physicians might misjudge patients' desire for active involvement in their handling.

A 2016 report focused on ulcerative colitis patients who faced two handling options with meaning, life-altering side effects.37 Researchers hypothesized that patients would be conflicted most the side furnishings of the treatments, but a patient preference analysis revealed otherwise. Patients were fundamentally concerned with the progression of their ulcerative colitis.38 These results demonstrated that doctors do not ever know what matters nearly to patients.

Other common barriers include the perception that shared determination making is already occuring, that patients don't desire it, that it is ineffective39 and that many patients cannot sympathize their options.40 According to a 2014 Altarum survey, 37 percent of physicians believe that patients want the physician to make the decisions regarding their medical treatment (with minimal input from the patient), simply only seven percent of patients selected this as the function they wanted doctors to have.41 Nearly 9 in ten consumers say if their doctor provides them with material when diagnosed with a health condition, they read it as soon as possible.42

Decision Aid Shortcomings

The employ of conclusion aids is a key component of PSDM. Providers take reported that decision aids increase cohesion amidst squad members (including patients) and facilitates patient education in both clinical and telemedicine settings.43 But decision aids are but effective if they are accurate and present the data in ways that patients with varying literacy levels, language and cultural backgrounds tin understand. For example, some Latina patients were more responsive to a patient decision aid designed equally a short soap opera that tells the story of a person in a similar situation.44

Some other challenge for patient decision aids is to continue pace with rapidly changing developments, including new handling alternatives and new information concerning treatment efficacy and complications. Although the International Patient Decision Assistance Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration has created a standard checklist45 for high-quality decision aids, in that location is currently no national torso responsible for certifying decision aids that adhere to the checklist. Certification helps providers, patients and payers evaluate the quality of conclusion aids and is needed to ensure that decision aids are unbiased, comprehensive, accurate and up-to-date.46 Barriers to certification include the cost and laborious process of certifying materials.

Provider Time Constraints

Fourth dimension constraints remain the nearly frequently cited barrier to implementing shared decision making in clinical practice.47 Specifically, time pressures make it difficult to listen to patients, address their needs and emotional concerns and help them make decisions that are consistent with their values and preferences.

PSDM's impact on consultation length is unclear, as studies have shown both increases and decreases in consultation length afterwards patients have viewed a decision assistance.48 More than enquiry is needed to sympathize the impact of shared determination making on providers' work schedules.

Provider Reimbursement is Not Aligned with PSDM

Some other barrier to integrating PSDM into common practice is that fee-for-service payment systems do not typically reimburse clinicians for fourth dimension spent engaging with patients in shared decision making.49

At that place has been considerable debate over whether to reimburse providers for participating in PSDM or if PSDM should exist function of routine care that is not reimbursed separately. As noted above, PSDM's impact on consultation length is unclear, leaving the implications for reimbursement cryptic.fifty Also debated is the type of providers that should appoint with the patient (specialist, primary care or nurse) in PSDM.

Regardless of reimbursement, wellness systems have struggled to supply hospitals and other care settings with sufficient resources (such as decision aids or education campaigns for patients and providers) to incorporate PSDM into the intendance procedure.

Provider Training

PSDM training has has been shown to increment provider's confidence and knowledge, enabling them to facilitate PSDM more easily.51 In that location are currently 83 preparation programs in the Us but, due to providers' and health systems' attitudes towards PSDM, these programs are not widely used.52

Malpractice Liability

Some other challenge that is specially concerning to hospitals and providers is medical malpractice. Patients may be more than likely to sue if they choose not to have procedures or screening through PSDM, but develop a more serious condition later on on.53

Concerns nearly medical malpractice are less common amidst providers than concerns about time constraints and applicability of PSDM to clinical situations. I study found that using a decision aid in conjunction with PSDM offered protection for physicians against a malpractice ruling in a mock trial.54 Although the bear on of PSDM on malpractice lawsuits is ambiguous, information technology remains a business.

Best Exercise Strategies to Implement PSDM

The Patient's Part

Providers must recognize that patient preferences vary with respect to being actively involved in their care.

The vast majority of Americans (86%) trust their doctor.55 For some, this results in a reluctance to have a more agile role in their care. 56 Still, many patients express dissatisfaction with their md considering they practise not feel that they accept had adequate input into their providers' decisions about their health.57

One factor that contributes to this problem is that patients often do not know enough about their handling options to make informed decisions. Nigh consumers (95%) believe information technology is important that doctors tell them almost the results of medical research when making treatment decisions.58

As described to a higher place, patient decision aids are a strategy to guide the patient in the development of their care plan. To further open lines of communication, researchers recommend encouraging patients to ask their providers three or four general questions when discussing handling options. These include: "What are my options?" "What are the benefits and harms?" "How likely are negative effects?" and "What will happen if I practise null?" This strategy lonely has been shown to ameliorate both the consultation process and patient outcomes.59

Patients will continue to have different preferences when information technology comes to beingness involved in their care. All the same, there is stiff prove that more engaged patients take better wellness outcomes and intendance experiences.lx Thus, PSDM should guide patients to the extent to which they are comfortable.

The Provider'southward Part

Assessing a patient's personal preferences should begin with determining how large of a role the patient wants to play in his or her care. Clinicians should assess these values at the starting time of the care procedure and design their handling approach accordingly.61 They must uncover the motivating factors that drive a patient's decision rather than brand assumptions.

Using determination aids can help clinicians more than efficiently elicit patients' preferences. Some providers will demand to arroyo the clinical interaction in a new way, giving upward their authoritative role and becoming more than effective coaches or partners. The ability to ask, "What matters to you lot?" likewise every bit "What is the thing?" tin go a long fashion in beginning a fruitful dialogue.62

Electronic medical records can provide breezy training by identifying patients who will be facing a medical determination and reminding providers to offering patients decision aids and appoint in a PSDM chat.63

Three chief motivators help providers implement shared decision making in clinical do: (one) health professionals' internal motivation, (2) the perception that practicing shared conclusion making will lead to improved patient outcomes and (3) the perception that practicing shared decision making will lead to improved healthcare processes.64 These motivators may need to be leveraged to shift providers' attitudes towards PSDM.

The Caregiver'south Role

As with many aspects of patient care, involving family members and caregivers is important. Patients lean on their loved ones during times of uncertainty and poor health.

Involving family members in the intendance controlling process is a primal strategy to supporting high-quality patient care and delivering a positive experience. Strategies to appoint families and caregivers in shared decision making are similar to those that strive to appoint individual patients. Providers need to offering ample data to support the decision at hand and embrace a patient- and family centered approach. Clinicians must too take into business relationship the patient'south preferences for family unit interest. In some cases, patients may not want high levels of family engagement.

Conclusion

Given the fact that PSDM has considerable advantages and few disadvantages, it is used far too infrequently. As noted above, in a study of more than one,000 office visits involving more than than 3,500 medical decisions, less than 10 percentage of decisions met the minimum standards for shared decision making.

In the attempt to create a high quality, patient-centered healthcare system, policymakers, payers and healthcare facilities should brand shared conclusion making the standard of care for all clinical encounters with more than one medically appropriate path forrad.

Success in this attempt volition require proactively addressing the barriers described in this research brief, such equally lack of physician purchase-in, lack of time, lack of reimbursement, poor integration into clinical workflows and a scarcity of information designed for patient use. Grooming programs, educational materials and inclusive dialogue can assist providers and patients brand PSDM a routine component of patient-centered care.

Notes

i. Ditre, Joe, Consumer-Centric Healthcare: Rhetoric vs. Reality, Healthcare Value Hub, Inquiry Brief No. xviii (May 2017).

2. Patient Advocate Foundation, The Roadmap to Consumer Clarity in Health Care Determination Making (2017).

iii. Légaré, France, and Holly O. Witteman, "Shared Decision Making: Examining Key Elements and Barriers to Adoption into Routine Clinical Practice," Health Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 2 (February 2013).

4. Barry, Michael J., and Susan Edgman-Levitan, "Shared Decision Making—The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care," NEJM, Vol. 366 (March 2012).

5. Ibid.

half dozen. National Quality Forum, Shared Decision Making: A Standard of Intendance for All Patients, Washington, D.C. (2017).

7. Barry (March 2012).

viii. Stacey, Dawn, et al., "Decision Aids for People Facing Wellness Treatment or Screening Decisions," Cochrane Database (Oct 2011).

ix. Ibid.

10. Ernst, Alexandra, et al., Shared Decision Making: Engaging Patients to Better Wellness Care, Families USA, Washington D.C. (May 2013).

eleven. Ha, Jennifer F., et al., "Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review," The Ocshner Journal (2010); Ditre (May 2017).

12. Légaré (February 2013).

thirteen. Elwyn, Glyn, et al., "Shared Decision Making: A Model for Clinical Practice," Journal of Full general Internal Medicine, Vol. 27, No. x (May 2012).

fourteen. Choudhary, Anjali, and Vineeta Gupta, "Educational activity Communications Skills to Medical Students: Introducing the Fine Art of Medical Practice," International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research (Baronial 2015).

15. Berman, Amy, "Living Life in My Own Style—And Dying That Way As Well," Health Affairs (April 2012).

16. "Shared Determination Making Leads to Ameliorate patient Outcomes, Higher Satisfaction Rates," News Medical Internet. https://www.news-medical.net/news/20170314/Shared-decision-making-leads-to-better-patient-outcomes-higher-satisfaction-rates.aspx (accessed March 17, 2018) and https://world wide web.aaos.org/AAOSNow/2015/Jan/managing/managing2/?ssopc=1

17. Ibid.

eighteen. Ibid.

19. Dobler, Claudia, et al, "Can Shared Decision Making Improve Physician Well-Being and Reduce Burn-Out?" Cureus (Baronial 2017).

20. Peek, Monica, et al., Patient Trust in Physicians and Shared-Decision Making Among African-Americans with Diabetes, National Institutes of Wellness (October 2012).

21. Légaré (February 2013).

22. Altarum Institute and Oliver Wyman, Right Place, Right Time Improving Admission to Health Intendance Information For Vulnerable Patients — Consumer Perspectives (Jan 2017).

23. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, The CAHPS Ambulatory Care Comeback Guide: Strategy 6I: Shared Decision Making, Rockville, Dr. (2017).

24. Stacey, Dawn, et al., "Decision Aids for People Facing Wellness Treatment or Screening Decisions," Cochrane Database (April 2017).

25. Veroff, David, et al., "Enhanced Support for Shared Decision Making Reduced Costs of Intendance for Patients with Preference-Sensitive Weather condition," Health Affairs, Vol 32 No. 2 (Feb 2013).

26. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Beneficiary Engagement and Incentives Models: Shared Determination Making Model, https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-12-08-2.html (accessed March 14, 2018).

27. O'Malley, Ann S., et al., Policy Options to Encourage Patient-Md Shared Decision Making, National Establish for Health Care Reform, Washington, D.C. (September 2011).

28. Shafir, Adi, and Jill Rosenthal, Shared Decision Making: Advancing Patient-Centered Care Through State and Federal Implementation, National Academy for Land Health Policy, Washington, D.C. (March 2012).

29. Ibid.

30. Kennedy, Andrew, et al., "Furnishings of Decision Aids for Menorrhagia on Treatment Choices, Wellness Outcomes, and Costs," JAMA, Vol. 288, No. 21 (January 2003).

31. Arterburn, D., et al., "Introducing determination aids at Group Wellness was linked to sharply lower hip and genu surgery rates and costs," Health Diplomacy, (September 2012).

32. Lee, Emily O., and Ezekiel J. Emmanuel, "Shared Decision Making to Improve Care and Reduce Costs," NEJM, Vol. 368 (January 2013).

33. Braddock, Clarence H., et al., "Informed Conclusion Making in Outpatient Practice," JAMA Network (December 1999).

34. Ibid.

35. Agency for Healthcare Enquiry and Quality, The CAHPS Ambulatory Care Comeback Guide, Rockville, Medico (December 2017).

36. Légaré, France, et al., "Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Shared Conclusion Making in Clinical Practise: Update of a Systematic Review of Health Professionals' Perceptions," Patient Education and Counseling, Vol. 73, No. three (Baronial 2008).

37. Heath, Sarah, "How to Include Patient Preferences in Shared conclusion making," Patient Engagement HIT (Aug. i, 2016).

38. Ibid.

39. Légaré (August 2008).

forty. Lynch, Wendy, Kristin Perosino and Michael Slover, Altarum Institute Survey of Consumer Healthcare Options, Altarum (Fall 2013).

41. Ibid.

42. Harris Poll, Consumer Attitudes Almost Health Study (March 30, 2016).

43. Griffith, Michelle, et al., "A Shared Controlling Approach to Telemedicine: Engaging Rural Patient in Glycemic Management," Periodical of Clinical Medicine, Vol. 5 No. 11 (November 2016).

44. Ernst (May 2013).

45. International Patient Determination Aid Standards, Criteria for Judging the Quality of Patient Decision Aids (2005).

46. Shafir and Rosenthal (March 2012).

47. Légaré (Baronial 2008).

48. Ibid.

49. Hibbard, Judith and Helen Gilburt, Supporting People To Manage Their Health: An Introduction To Patient Activation, The Rex's Fund (May 2014).

50. Ibid.

51. Ibid.

52. Diouf, Ndeye, et al., "Preparation Health Professionals in Shared Conclusion Making: Update of an international Environmental Browse," Scientific discipline Directly, Vol. 99, No. 11 (Nov 2016).

53. Durand, Marie-Anne, et al., "Can Shared Decision Making Reduce Medical Malpractice Litigation? A Systematic Review," BMC Health Services Inquiry (April 2015).

54. Barry, Michael J., et al., "Reactions of Potential Jurors to a Hypothetical Malpractice Suit Alleging Failure to Perform a Prostate-Specific Antigen Exam," Periodical of Law, Medicine, and Ethics (June 2, 2008).

55. Healthcare Value Hub, Consumer-Centric Healthcare: Opting for and Choosing Among Treatments, Easy Explainer No. 10 (2017).

56. Ibid.

57. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, The CAHPS Ambulatory Care Comeback Guide, Rockville, Md (December 2017).

58. Healthcare Value Hub, Consumer-Centric Healthcare: Opting for and Choosing Among Treatments, Easy Explainer No. 10 (Dec 2017).

59. Ibid.

threescore. Hibbard, Judith H., and Jessica Greene, "What the Evidence Shows virtually Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes and Care Experiences; Fewer Data on Costs," Health Matterdue south, Vol. 32, No. 2 (February 2013).

61. The Agency for Healthcare Inquiry and Quality developed the SHARE Approach and other tools equally a resource for providers: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/pedagogy/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/alphabetize.html

62. Barry (March 2012).

63. Shafir and Rosenthal (March 2012).

64. Ibid.

Source: https://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/advocate-resources/publications/consumer-benefits-patient-shared-decision-making

0 Response to "Why Is It Important to Integrate Both Evidence-based Practice and Patient and Family Preferences?"

Postar um comentário